Economization for Richer or Poorer

Action is behavior with a purpose, goal, or end. That which is used in action to pursue ends are means. The total quantity of a means available to an actor is called the actor’s stock of the means.

When a means, given the existing stock, cannot be used to compatibly pursue all possible ends that people (whether one person or many) may have for it, that condition is called scarcity, and the means is thereby scarce. In other words, something is scarce when using it uses it up in some way. Scarcity is a pervasive, inescapable fact of life in reality.

An individual’s use of scarce resources necessarily entails choices between incompatible ends. Some ends must be selected, and others sacrificed. A choice can also be said to be a trade-off or an exchange. The sacrificed ends are exchanged for the selected ends.

With incompatible ends for a given means, some ends must be pursued by being apportioned some of the means, and other ends left un-pursued. This selective and renunciative allocation of means among ends is called economization. The fundamental challenge of human life is economization: rationally dealing with the scarcity that pervades reality.

Value of Ends

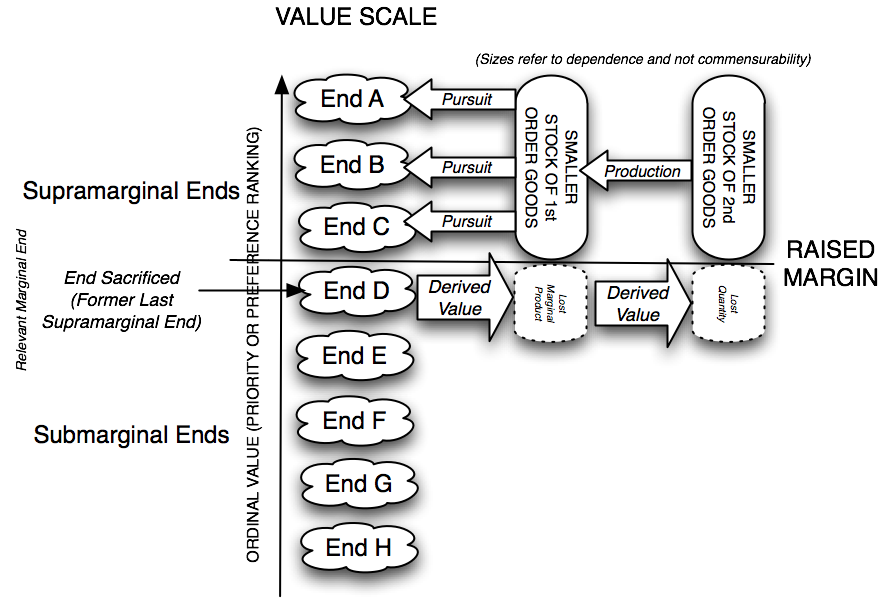

Economization, the allocation of means to competing ends, necessarily involves the prioritization of those competing ends. Some ends are pursued (apportioned some of the means), which are prioritized over other ends which are left un-pursued (apportioned none of the means). The ends pursued on one hand, and the ends un-pursued on the other, may be separated by an imaginary line called a margin. The ends pursued may be called supramarginal ends; they are above the margin. The ends left un-pursued may be called submarginal ends; they are below the margin.

FIGURE 1

A use to which some of a means is allocated to pursue a supramarginal end is a supramarginal service. A use that would be in pursuit of a submarginal end to which none of a means is allocated is a submarginal service.

The supramarginal ends can be ranked according to their priority with regard to means allocation. If some quantity of the means were lost, the end that would be sacrificed last is ranked first and placed highest above the margin. The end that would be sacrificed second to last is ranked second and placed second highest above the margin, etc.

The submarginal ends can be ranked similarly. If an additional quantity of the means were gained, the end that would be taken up (made supramarginal)first is ranked first below the margin. The end that would be taken up second is ranked second below the margin, etc.

This hierarchy of ends is called a value scale. The further up the scale an end is, the higher it is said to be valued. Notice that value is a relative preference ranking, and not an absolute quantity of any kind. In other words, value is purely ordinal, and not in any way a quantity that can be measured or expressed with cardinal numbers.

FIGURE 2

The ends that would be sacrificed first upon losing any given quantity of the means are the last supramarginal ends. The last supramarginal ends are, by definition, the least valued of the pursued ends. These ends may be calledmarginal ends, as they are “on the margin (edge)” at the bottom of the list of pursued ends, and will be the first to “fall off the edge” and become submarginal once the stock of the means is decreased. The uses to which a means is allocated to pursue the last supramarginal ends are the last supramarginal services. The last supramarginal services are the relevant marginal services when considering a decrease in the stock of a means.

The ends that would be taken up first upon gaining any additional given quantity of the means are the first submarginal ends. The first submarginal ends are, by definition, the most valued of the otherwise un-pursued ends. Those ends may also be also be called marginal ends, as they are also “on the margin (edge)” at the top of the list of un-pursued ends, and will be the first to “gain footing on the edge” and become supramarginal once the stock of the means is increased. The uses to which a means is allocated to pursue the first submarginal ends are the first submarginal services. The first submarginal services are the relevant marginal services when considering an increase in the stock of a means.

FIGURE 3

Value of Means

The utility (or usefulness, or serviceableness) of a means is the value of the ends that the means enables the actor to pursue. Means themselves are only valued insofar as they are useful in the pursuit of ends. Therefore, the value of a means is based on, and varies directly with, its utility.

The utility of a means is nothing but the value of ends pursued with it. Therefore, since utility is nothing but value looked at from a certain perspective, utility is, like all value, purely ordinal, and not in any way a quantity that can be measured or expressed with cardinal numbers.

A means has a different utility in each service that some of the means is apportioned to. The utility of means-quantity in each service is the value of the ends pursued by the means-quantity in that service.

The marginal utility of a means-quantity is its utility in its marginal service, which is the value of the marginal ends that depend on that given quantity. And, again, the marginal ends that depend on that given quantity are either the last supramarginal ends in the case of means already in the actor’s stock, or the first submarginal ends in the case of means not yet in the actor’s stock. Therefore, the value of any given amount of a means in an actor’s stock is based on, and varies directly with, its marginal utility.

As the stock of a means decreases, the margin is pushed higher, and ends progressively “fall of the edge;” and as the margin rises, ends of progressively higher value become the relevant marginal ends. Therefore, the less of a means in an actor’s stock, the more valuable are the ends the pursuit of which depend on any given portion of it: that is, the higher is that portion’s marginal utility, and thereby the higher is its own value.

As the stock of a means increases, the margin is pushed lower, making ends progressively “gain footing on the edge.” As the margin sinks, ends of progressively lower value become the marginal ends. Therefore, the more of a means in a person’s stock, the less valuable are the ends the pursuit of which depend on any given portion of it: that is, the lower is that portion’s marginal utility, and thereby the lower is its own value.

In sum, the value of a means-quantity depends on its marginal utility, which varies inversely with the size of the stock of that means. This is the Law of Marginal Utility.

This is, at this point in the analysis, clearly true for means which are used to directly pursue ultimate ends. An end which is not itself also a means to some other end is an ultimate end. A means that is used to directly pursue an ultimate end is a consumption good. The use of a consumption good is calledconsumption. A definite way of dedicating a good directly to consumption is aconsumption service.

Value of Higher-Order Means

The making of new means is called production. The means used in an act of production are called factors. The means produced in an act of production are called products. A factor can itself be the product of a previous act of production. And a product can itself be a factor in a future act of production.

A means that serves as a factor for the production of other means is aproduction good. Factors which are used together to produce a product are called complementary factors (with regard to each other). A production good that is itself produced is a capital good. A production good that is not produced is an original production good. This includes human bodies and land, which includes goods found in nature. Human body services are called labor.

Consumption goods can also be called first order goods, and their uses calledfirst order services. Production goods, when used to produce consumption goods are second order goods, and their uses called second order services. Production goods, when used to produce second order goods are third order goods, and their uses called third order services, and so on.

Production goods are different from consumption goods in that, as means, they only are used to pursue ultimate ends indirectly. For the use of a production good in an act of production, the immediate end is always its product (a good of the next-lowest order), the penultimate end is always a consumption good, and the ultimate end is always the end that the consumption good is used to pursue.

Now, the set of phenomena that are purposeful is called the realm of action.The subset of the realm of action that includes human action is called human affairs. Action does not include non-purposeful change. Non-purposeful changes are called natural phenomena. The set of natural phenomena is called the realm of nature or, simply, nature.

The undertaking of production is an action, and is therefore part of the realm of action. But the physical processes set in motion when undertaking production are in the realm of nature. Nature is characterized by regularity in its phenomena; identical occurrences in identical situations yield identical results. If it were not, the world would be too chaotic for action to be possible.

Therefore, a combination of factors of production, whenever they re-occur in the same exact way, will have the same results in their physical product, regarding both the product’s physical characteristics and quantity. Therefore, it is possible to know how much of a physical product is dependent on the contribution of any factor-quantity.

In a combination of factors, the quantity of the physical product that depends on a given quantity of one of those factors is the marginal product of that factor-quantity. In other words, the marginal product of a factor-quantity is the quantity of the product that would be forgone (not be produced) if that factor-quantity were removed from the stock, and thus left out of the production process.

The utility of a means-quantity in a production service, as is the utility of a means-quantity in any use, is the value of the ends that depend on it. What, then, is the end of a means-quantity in a production-service? Again, the immediate end of any act of production is the product. Therefore, the immediate end of a means-quantity in a production-service is its marginal product. And so, the utility of a means-quantity in a production-service is the value of its marginal product in that service.

The question then arises: what, in turn, determines the value of that marginal product? As with the valuation of all means-quantities, the answer is: its own marginal utility, which is the value of the marginal ends that depend on it. If the immediate marginal ends that depend on it are ultimate (consumption) ends, then its marginal utility is the value of those marginal consumption ends. If, alternatively, the immediate marginal ends that depend on it is thefurther production of yet more means, then its marginal utility is the value of its own marginal product. And the value of this marginal product is, in turn, explained exactly as above. This value derivation always ultimately terminates in its origin, which is the value of ultimate (consumption) ends.

More concisely, the utility of a good (means)-quantity in a 2nd order service is the value of its marginal product, which consists of a 1st-order good-quantity. The value of that 1st order marginal product in turn depends on itsown marginal utility, which, as explained above, is the value of the marginal consumption end that depends on it. Thus, the utility of a good-quantity in a 2nd-order service is ultimately based on the value of the indirectly pursuedconsumption ends that depend on it.

The utility of good-quantity in a 3rd order service is the value of its marginal product, which consists of a 2nd order good-quantity. The value of that 2nd order good-quantity in turn, as explained above, depends on its own marginal utility, which is the value of its own marginal product, which consists of a 1st order good-quantity. The value of the 1st order marginal product, again, depends on its own marginal utility, which is the value of the marginal consumption end that depends on it. Thus, the utility of a quantity in a 3rd-order service is also ultimately based on the value of the indirectly pursuedconsumption ends that depends on it.

This reasoning can be extended to any order of production. Thus, the utility, and therefore the value, of a quantity of a means in a production service of any order is ultimately based on the value of the indirectly pursued consumption ends that depend on it. We may call this the Law of Backward Value Imputation. This law is true for production services of any order, no matter how high; even for, say, production services of the five-thousandth order.

FIGURE

Indirectly-pursued ultimate ends are ranked in the same value scale as directly ultimate pursued ends when considering the allocation of a means stock. When economizing a stock of a good, an actor may allocate some portion of the stock to a 1st order use, some portion to a 2nd order use, some to a 49th order use, etc. He does so, so as to pursue all of his supramarginal ultimate ends, whether directly or indirectly, and to leave un-pursued all of his submarginal ultimate ends.

Again, the value of a quantity of a means is based on its marginal utility, which is the utility of that quantity in its marginal service. If that marginal service is a certain production service of a certain order, then its marginal utility is the value of its marginal product in that service. Therefore both its value and its marginal utility are ultimately based on the value of the ultimate consumption ends that would depend on it in that service.

The Law of Marginal Utility applies to all means, whether they are used to directly (as consumption goods) or indirectly (as production goods) pursue ultimate ends, or both. The less of a means in a person’s stock, the more valuable is the ultimate end (whether pursued directly or indirectly) that depends on any given amount of it: that is, the higher is its marginal utility. The more of a means in a person’s stock, the less valuable is the end (whether pursued directly or indirectly) that depends on any given amount of it: that is, the lower is its marginal utility.

This value theory, when applied to interpersonal exchanges, can be used to derive price theory, which can be used to derive profit-and-loss theory, which can be used to derive a general theory of the market.

Also published at Medium.com: